For the last two weeks we’ve talked about crafting a broadcast mix for your church and the various ways to set it up, whether it’s with your current FOH console or whether it’s with a separate console for broadcast. We’ve discussed analog vs. digital splits and now we come to the fun stuff. Actually mixing content. Now that we’ve got our mix options set up, whether it’s a feed from FOH or a split to a separate console, we need to get a good mix crafted. Before we dig into the good stuff, it’s worth noting that you should always keep track of the speech mics in the field and whether or not they should be on. If a speaker leaves his/her mic on while in the audience you may not hear anything different in the house but in the broadcast it will make a huge impact. This is another great reason to utilize automation to help you easily conquer the little stuff.

So, broadcast mixing typically needs to be a little more precise than FOH. Because we don’t have a large room to hide mistakes in, we need to be very conscious of various instruments and singers and how they’re blending with everything else. Typically I tend to mix the band a little heavier than vocals when doing broadcast because even with reverb and a band, it is often very easy to hear mistakes made by vocalists when singing. They’ve got one of the hardest instruments to control and keep in tune and even the best singers in the world aren’t perfect so I actually keep them in front, but not overtly so. I’m also constantly on the lookout for band members who may be struggling. You’ll also want to try different reverbs out and see what works best. Typically reverbs that work in an auditorium don’t work as well in broadcast. Try to find something that fits your mix and doesn’t tail too long. Too much reverb can render a vocalist unintelligible and it’s much easier to overdo it in broadcast than FOH. Mixing for broadcast is very different from mixing a room. As discussed earlier, it’s mainly different because you’re not dealing with interactions from the room and PA nearly as much as FOH has to. It’s also not quite like producing an album. It’s a blend of studio work and live sound. Broadcast mixing has it’s own challenges.

One main area broadcast differs from FOH is in EQ. EQ for broadcast is much easier in many cases because you aren’t fighting the room. This is where plugins can make a huge impact. If you’re using Waves you can use plugins like the F6 to dynamically carve or add frequencies back into channels, you can use the C6 or C4 to dynamically compress or expand bands of frequencies. We previously spoke of the fact that most listeners will be listening on phones and tablets and this is another area that comes in to play. We need to make sure we EQ in such a way that things sound pleasant on all devices. Because of that limitation we have to make sure we don’t have too much low end on channels that don’t need it and we should keep from having too much in the low-mids because that will really muddy up a mix on smaller speakers. We also have to remember that we aren’t filling up a big room, just a small pair of speakers or maybe headphones, so everything needs to be EQ’d as tight as possible. That being said, a lot of corrective EQ you might instinctively reach for at FOH, is not needed in broadcast. Mostly just watch your lows and low-mids. Inserting a plugin with an RTA on it like the F6 or HEQ can really help to monitor this as well.

Panning is another important tool in shaping a good mix for broadcast. When we’re listening on headphones or a small device, similarly to listening to a PA in a room, our brains need help to pick out all the various inputs in a mix. Panning can be a huge help in this area. With drums, I like to pan them from the perspective of the drummer so that the sound of each individual drum matches the sound of that drum in my overheads. This helps keep the sonic image clean but also sounds really cool on a mix when panned from left to right. It also helps with visuals if you have camera on the drummer and he plays from one side of the kit to the other. I’ll also pan instruments based on stage location and what they’re doing and I change it up from time to time as well. Singers are also usually slightly panned with any leaders being dead center. Be careful not to pan singers too drastically as it can cause certain singers to stand out too much. I also typically keep either the keyboard or acoustic guitar center depending on which instrument is the anchor for a particular song.

One other important part of the broadcast mix is audience mics. If you can have them at all, I would recommend it. It’s best to have them hanging in line with your PA and pointed at your main audience area but even choir mics hanging halfway back is better than nothing. Being able to get claps, cheers, laughs and singing from the congregation connects the broadcast audience with the audience in the room. The best place for an audience mic is either the lip of the stage or hanging over the lip of the stage pointed at the audience. Most broadcast guys go with the a shotgun mic like the Sennheiser 416 and will place anywhere from 2-4 depending on the room. I’ve seen as many as 8 handling a large crowd. If you don’t have the budget for new mics utilizing a condenser or even dynamic mic you already own will be better than nothing (just anything cheap and omnidirectional like this pair on Amazon). Try to get it as close to in-line with the PA as possible so you don’t have weird delay issues. Nothing sounds better than a well placed crowd mic picking up the congregation singing as the worship team falls back. Crowd mics can also be used to feed in ears for musicians so they can serve more than one purpose.

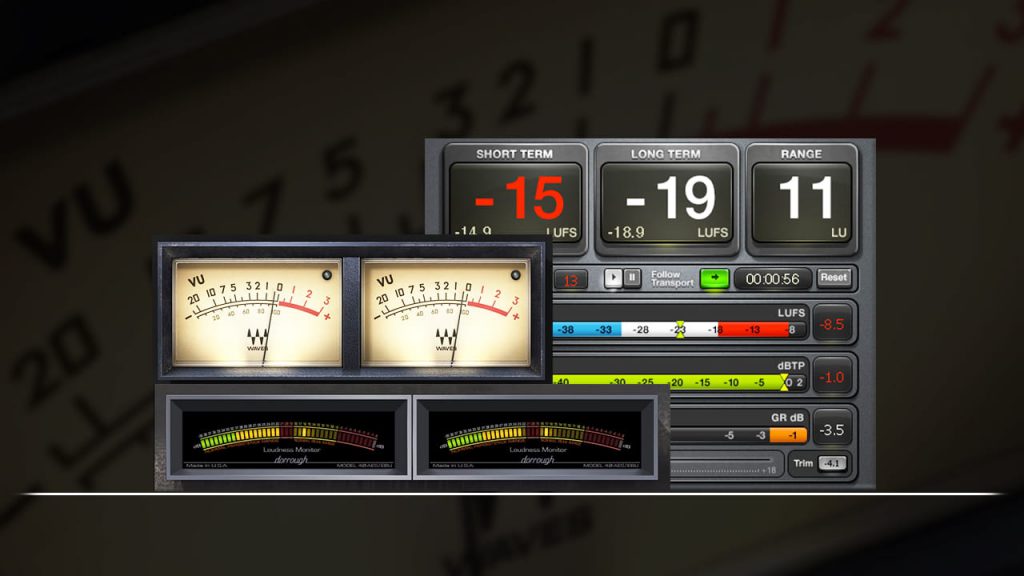

Unlike mixing a live PA where dynamics are incredibly important, in the broadcast world we must try to do a better job of keeping the loudness more uniform. If people have to turn the volume way up for the sermon or can’t even hear the sermon, then we’ve only done half our job. If you’re using your FOH console to mix you can accomplish this by using a post fade aux and turning all your musical channels down more and your speech channels up more, or doing the same with subgroups. For live events on broadcast on TV, your overall loudness is supposed to be within +-2db of -24LKFS (this is a measurement standard use to standardize perceived volumes across all devices) for the length of the program. While we aren’t necessarily required to do this for streaming online, I like to try to follow it as a good rule of thumb giving myself a range of +-3db LKFS. Getting consistent loudness on a separate broadcast console is a little easier and we have some better ways to do it as well. One of those ways is by using the WLM Meter plugin in waves to monitor (and if needed limit) the loudness of your mix. There are also several outboard options like this one that just allow you to monitor. The basic principle is to check three things: 1) level match speech vs music, 2) be sure to check for headroom across your entire signal chain, 3)If nothing else, take a recording of your mix and analyze it to see how you line up with the LKFS standard. No one is going to be angry that your mix is too quiet or too loud but getting things setup correctly can really contribute to the overall quality of the art you create.

At the end of the day, the best way to craft a mix is to just work at it. Like playing an instrument it takes time and practice. The more you do it the better you’ll become. Hopefully this series was a good primer and a first step towards better crafted mixes. If you have any questions or thoughts, please drop a comment below or on Facebook. As always, if you’ve enjoyed reading this blog, feel free to sign up at this link to subscribe and be notified when new content is available. We hope to see you next week!

P.S. – If you didn’t already notice have a new author, Justin Fugett! To help you get to know who is behind the scenes here I’ve launched a new page on the site with bios for each author. Be sure to check it out at this link!