Welcome to week three of our audio distribution primer. Up to this point we’ve covered the analog ways we distribute audio signal. This week we’ll discuss some of the most common digital audio transport formats currently in use and discuss items to consider when using them.

The first digital audio format I’d like to discuss is called AES3 and it’s one of the older and still very versatile audio formats in use today. The AES3 format or more often just referred to as AES was created in 1985 and refined as late as 2003. AES3 is basically a two channel format that allows two devices to communicate digitally between them. It typically uses a single XLR or BNC cable to connect the devices. AES3 can run from 44.1K to 192K depending on the device. Most newer consoles and devices can also reformat the bitrate so that a 96K device can talk to a 48K device well enough. Keep in mind when connecting to AES devices, that both devices have the same bitrate or that one or both can change their bitrate at need. AES has its advantages over analog because it is less susceptible to hums and buzzes and also keeps everything digital and keeps you from having to deal with gain staging as there are no preamps to deal with once in the digital realm. Many digital consoles for sale today will include a few AES ports on it’s local I/O, go take a look and see if you’ve got one!

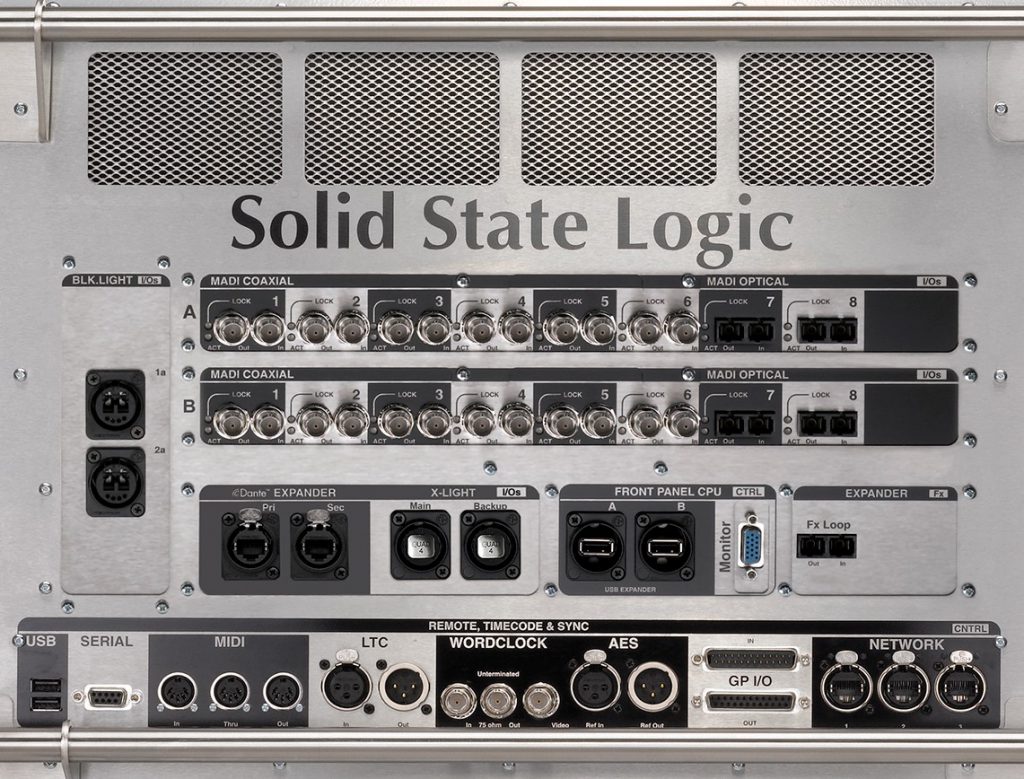

The second digital audio format is AES10, more commonly known as MADI. MADI is a 64 channel bidirectional format often found in broadcast applications for its ease of use and high channel count. MADI, like most other digital formats relies heavily on having the correct bitrate and having a single master clock. MADI is nice because along with it’s high channel count its fairly easy to diagnose problems. So long as you have the same bitrate between your two consoles (or other audio devices) and have the cables connected correctly, MADI tends to just work. There are no address to assign like with some other protocols. It’s a 1 to 1 connection so there’s very little to mess up. MADI typically uses BNC cables. One for sending and another for receiving. There are some CAT5 MADI devices but BNC and optical fiber are the most prominent in use today. Using fiber, MADI Can be run for thousands of feet or even several miles. MADI is a 48K native format but can be run at high bitrates with doubled cables and special cards or a halved channel count. There are also devices that can bridge MADI devices together without having to have a single clock master which allows for even greater flexibility, a lot of manufacturers make USB to MADI interfaces (i.e. – Madiface XT) which also allows for easy recording. Several console manufacturers use MADI as their default method of communication between stageboxes and consoles. Because of this MADI also has a 56 channel bidirectional mode where control commands for stage boxes can be sent using the bandwidth for the last 8 channels.

Another popular audio format still in heavy use is AES50. This is primarily used by Music Group companies; Midas, Behringer, and Klark Teknik. AES50 is another point to point network like AES3 and MADI, with the ability to carry 48 channels bidirectionally. AES50, like MADI and AES is dependent on clocking and sample rates. AES50 runs over a single cat5 cable and can be run up to 300ft or can be converted to fiber and run much longer. AES50 is a 48K native format but can be used at 96K with a halved channel count or doubled cable run. Midas PRO series consoles use AES50 in 96K mode and use a second cable to handle the higher channel count. AES50 like MADI, is point to point and doesn’t deal with addressing or extra computer programs for control. Also like MADI, AES50 is simple and easy to use for its ease of troubleshooting. There are multiple options of converting AES50 into other formats or even bridging AES50 networks but for the most part it is similar to MADI and is a great simple sound connection. The addition of AES50 to the Behringer X32 makes it especially powerful for its’ price range as the console can route two seperate AES50 streams through itself to other AES50 devices making for easy digital splits between consoles and other devices.

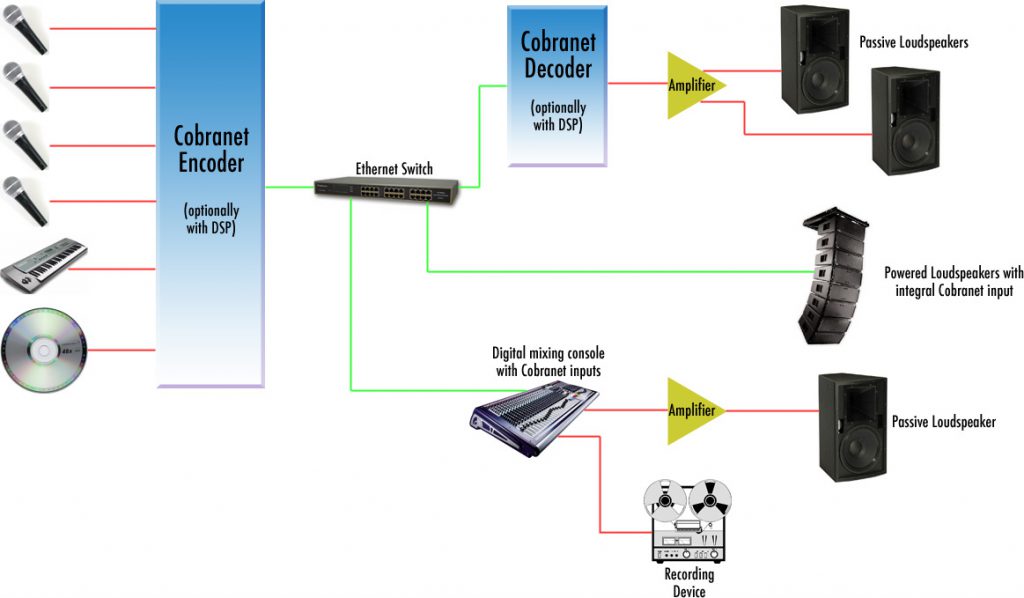

The next audio format for discussion is CobraNet. CobraNet was the first audio format to market audio over ethernet to the masses successfully. Starting in 1996 it offered the ability to send between 8 or 64 channels bidirectionally over cat5 cables at 48K uncompressed audio. At first it was limited to a bit depth of 16bits but eventually was able to offer bit depths of up to 24bit and sample rates of 48K and eventually 96K. CobraNet also had the ability to be networked but had many constraints. CobraNet is the progenitor to most modern networking formats today and was placed in many theaters studios and large event spaces where low channel counts needed to be delivered long distances (think delays speakers at festivals or opera houses). CobraNet works by assigning channel numbers to a sending device and then assigning channel numbers to a receiving device. This is typically done with software inside the device or with dip switches. This made it somewhat flexible and allowed for limited routing possibilities. Another feature of CobraNet was its ability to run over fiber via network switches so it could be run over very long distances and also be routed to various places without any of the usual pitfalls when running audio over long distances with copper wire.

The last format is a little lesser known and is not in much use anymore. EtherSound is a 64 channel network of 48K audio over a single cat5 cable developed in 2001. EtherSound is a proprietary format started by DigiGram and used by Yamaha for their LS9 and M7CL consoles and can be added to their other consoles by an option card. While many manufacturers made option cards and devices for EtherSound it was a little too ahead of its’ time. It could be networked on layer two switches and used a special program to patch channels similarly to the way Dante and AVB patch today. Unfortunately EtherSound didn’t gain a ton of popularity and is not in wide use in the wild. Even with the help of Yamaha’s pervasive console sales EtherSound never caught on in the way that newer digital network formats have today. Personally, I think that it was just a little ahead of its’ time and implemented in a clunky way that scared too many technicians early on. I’ve worked with this technology and it’s actually pretty cool but it can be finicky for the end user.

Both EtherSound and CobraNet work by dividing the audio into data packets and sending them out (just like your computer does when sending files over the internet) and then separating the packets at the other end and converting them to another digital format or to analog audio depending on the application desired. These are two (CobraNet and Ethersound) “true” audio networking standards where AES3, MADI, and AES50 are all still point to point connections. Next week we will continue to dive into audio networking as we discuss the Dante and AVB formats which are the most widely used formats in use today. If you want to be sure not to miss it, subscribe at this link, and we’ll be sure to send you an email when next week’s post goes live! If you have any questions about what was discussed today, be sure to drop a comment below or hit us up on facebook! See you next week!